Spring's Creation

You can listen to this week's playlist here.

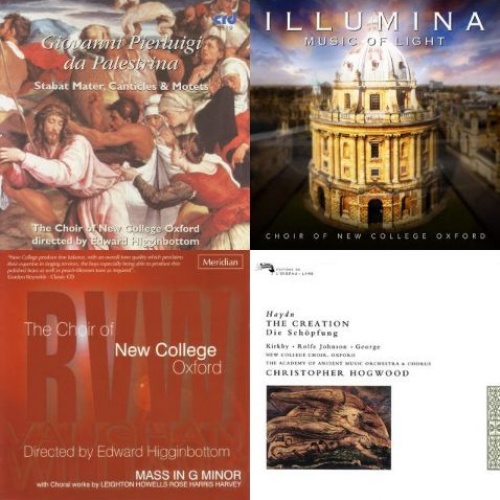

During this week's playlist, we’re taking a look around, enjoying the splendour of the world now revealing itself in its bright Spring garments—including quite a bit of rain, in Oxford at least. A subsisidary theme of division and unity has revealed itself in the selection, too. Our trip around the New College Choir discography begins at the very beginning, with Haydn’s The Creation and its most joyful chorus, which comes just after the creation of the sun. Over the years the choir has collaborated with several period instrument orchestras and distinguished conductors: on this recording from 1991, the Academy of Ancient Music and Christopher Hogwood. A more nuanced reading of creation may be found in Gerard Manley Hopkins’s poem God’s Grandeur. Hopkins has a sensitive partner in Kenneth Leighton, who manages to set the text in a fully contrapuntal texture, while never losing clarity—and what an ending! A miniature masterpiece, I think. By contrast, Eric Whitacre’s music moves in long chordal waves of sound; or perhaps a better metaphor would be beams of light. Back, then, to the source of so much of the choral music tradition: the classic polyphony of the Renaissance, and arguably its most sophisticated practitioner, Palestrina. In this Magnificat, the musical line – the argument set out, if you like – is passed between groups of voices, usually equally divided into two halves, in the same way as we are physically positioned in our chapel stalls. Just occasionally – right at the end, and once before at the words ‘omnes generationes’ the eight vocal parts are united in grand homophony. In this music we may observe not only a counterpoint of harmony (i.e. articulated through pitches and rhythms), but a wider counterpoint of texture, of the warp and weft of sound itself.

Next, a rarity among Britten’s sacred choral music: his Antiphon of 1956. This setting of Herbert’s ‘Praisèd be the God of love’ (not the poem ‘Let all the world’, also called Antiphon) connects with the Eastertide theme of the Good Shepherd, and is most obviously antiphonal in its pitting of a treble soloist against the full choir. Like Leighton’s motet, it has a magical ending, in which an F major triad sung by a trio of trebles to the word ‘one’ eventually achieves unity with the lower voices, who sing ‘two’ on a series of triads dissonant with the trebles’. Herbert’s poem is a riff upon Jesus’s promise in John 10 that there

will be ‘one flock and one shepherd’, and it is from the same Gospel that the next motet takes its text: in the so-called Farewell Discourse given to the disciples before the Passion. Matthew Martin wrote this motet for the choir’s visit to the Vatican, where we sang it at the Offertory during the Pontifical Mass on St Peter’s Day, 2015. The brief was that we should sing a piece of no more than four minutes, in English, on the subject of unity…drawing a blank in the extant repertory, I reached for my phone, and here is the result.

The psalms, especially at the very end of the book, include several evocations of creation rejoicing in its maker, and the final two works on our playlist (mostly) mine this, the richest source of texts for composers of sacred music. Mendelssohn’s charming motet Laudate pueri Dominum (in two movements, the second leaving us feeling perhaps that a few subsequent pages must have been lost) takes the opening words from Psalms 113 and 128 respectively. A wider-ranging approach to texts is taken by Parry in his long anthem, Hear my words, ye people—mostly from the psalms, but also raiding Job and Isaiah. I think our recording is the only one to use four soloists (only) in the quartet that sings much of the text, and in antiphony with the full choir, and in two impressive solo ‘arias’ for bass and treble respectively. Most thrilling perhaps is their exchange of ‘Amen’ phrases, and their eventual union, at the very end; here Parry sets a paraphrase of Psalm 150 to what has become the hymn tune Laudate Dominum: ‘O praise ye the Lord’, which embraces both of this week’s themes with admirable concision.