The English Tradition

You can listen to this week's playlist here.

This week’s playlist is the first in a two-part survey of what is often referred to as the ‘English Choral Tradition’. We’ll proceed in chronological order, but both playlists will be topped and tailed by related works. This is not a story of an isolated exceptionalism, but one of cross-fertilisation between this country and its continental neighbours: and the opening piece is a case in point. At the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, the court of Charles II modelled itself on that of Louis XIV, the ‘Sun King’ of France—not least in the provision made for music in the Chapel Royal. When Charles was succeeded by his brother James, the coronation on 23 April 1685 featured some of the finest music ever to have graced such a ceremony: principally by John Blow and Henry Purcell. The lavish scoring of their anthems God spake sometime in visions and My heart is inditing, with eight or more vocal lines (possibly doubled by wind and/or brass) and opulent string symphonies, spoke of confidence in the home-grown talent, which had sprung up in fairly short order after the fallow years of the Commonwealth. Strikingly, these two anthems follow almost identical structural schemes, suggesting either that the younger Purcell modelled his on Blow’s, or – just as likely – that these close colleagues compared notes. Which is better? It’s a matter of taste, but I must confess that, in this comparison, Blow wins every time for me.

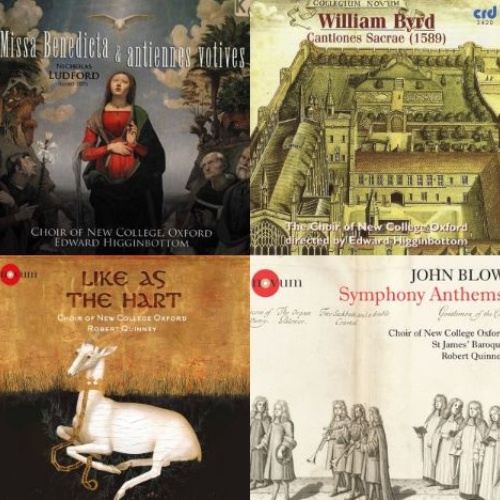

At the Reformation, the first music to be composed for the re-established Anglican liturgy (by composers such as Henry Cooke and William Child) was broadly similar in style to the music of the early 17th century, some of which we’ll hear later on. That music, by Gibbons, Tomkins and their contemporaries, was itself strongly rooted in the classic modal polyphony of the previous century, by composers such as Palestrina and this country’s own William Byrd. This music – concise, tightly argued, tersely rhetorical – is thus perhaps closer to what Charles II heard in 1660 than it is to the music Byrd would have known as a choirboy, in the florid English pre-Reformation style we hear in Ave cujus conceptio by Nicholas Ludford (d. 1557). This exquisite votive antiphon is a late flowering of the genre that had come to dominate the non-Mass Ordinary repertory for choirs in England in the early sixteenth century. Typically for a composer of Ludford’s generation, the super-florid melismata of the earlier Eton Choirbook style have been trimmed somewhat, and there is tighter, closer imitation between voices. But this is still the music befitting a soaring late-Gothic space such as the chapel of King’s College, Cambridge, or St Stephen’s in the Palace of Westminster, where Ludford himself worked.

Then everything changed. With a few strokes of the theological and bureaucratic quill, Church music was suddenly shorn of its transcendence, and rethought entirely, as a modest, close-fitting garment for the Word of God. Our next track typifies the new insistence upon syllabic word setting, so the text may be heard and understood by any listener. This is Psalm 42, paraphrased by (or under the patronage of) Elizabeth I’s first Archbishop of Canterbury Matthew Parker, and set to music by Thomas Tallis. It is quite unlike Ludford’s arching polyphony, but it is, in its own way, just as beautiful.

If Tallis was – in the tunes for Parker’s psalter – under the influence of the Calvinist reformers, his younger colleague William Byrd took his cue from the latest music of continental Europe. This is arguably as true of his madrigalian Anglican service music and anthems as of the more obviously ‘continental’ Latin polyphony that he published: here I’ve included a superb example of the latter, the motet O quam gloriosum from his 1589 collection. These motets could never have been sung in an Anglican setting, not even in the relatively ornate liturgy of Elizabeth’s Chapel Royal. Rather, they were perhaps appreciated by connoisseurs in domestic situations, like songs and madrigals: and those in the know might well have appreciated the recusant subtext of Byrd’s collections. The ‘glorious kingdom’ of this motet contains ‘all the saints’, and perhaps particularly in Byrd’s mind, the white-robed army of martyrs. The madrigalian expressive immediacy of Byrd’s music feeds directly into the work of Orlando Gibbons (1583-1625), whose See, see, the Word is incarnate takes in the whole of the earthly life of Christ, from birth to Ascension. And Gibbons’s music must still have been in the repertory after the Restoration of 1660, if the verse anthems of John Blow and his contemporaries are anything to go by. When the Son of Man shows this direct line of descent, while incorporating some of the rhetoric of what came to be called ‘Baroque’ music. You probably won’t have heard this piece before, unless you happen to have listened to our Blow recording of 2015: it has never been published, let alone recorded before, and one of the solo parts (Contratenor Decani) is missing in the sources, and was reconstructed for this project.

Blow brings us back to Purcell, and My heart is inditing. Stay tuned for Part 2, next week!